Compared with HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2 significantly improves the performance of web pages. Just upgrading to this protocol can reduce a lot of previously required performance optimization work. Nevertheless, HTTP/2 is not perfect, HTTP/3 was introduced to solve some of the problems that exist in HTTP/2.

Defects of HTTP1.1

High latency — Head-Of-Line Blocking

Stateless feature — impediment to interaction

Plain text transmission — insecurity

Does not support server push

High latency — reduces page loading speed

In recent years, although network bandwidth has grown very fast, we have not seen a corresponding reduction in network latency. The main problem of network latency is due to Head-Of-Line Blocking, which results in bandwidth not being fully utilized.

Head-Of-Line Blocking refers to when a request in a sequentially sent request sequence is blocked for some reason, all requests lined up behind it are also blocked, leading to the client receiving data late. To solve the problem of Head-Of-Line Blocking, people have tried the following methods:

Distribute resources of the same page to different domain names to increase the connection limit. Chrome has a mechanism that allows six persistent TCP connections to be established simultaneously for the same domain name by default. When using persistent connections, although a TCP pipeline can be shared, only one request can be processed at the same time in one pipeline. Other requests can only be blocked until the current request is finished. Moreover, if there are 10 requests happening simultaneously under the same domain name, then four of the requests will be queued waiting until the ongoing requests are completed.

Merge small files to reduce the number of resources. Sprite merges multiple small images into a large image, and then “cuts” the small images out again using JavaScript or CSS.

Inlining resources is another trick to prevent sending many small image requests, embedding the original data of the image in the URL inside the CSS file, reducing the number of network requests.

Reduce the number of requests. Concatenation combines multiple small JavaScripts into one larger JavaScript file using tools like webpack. But if one file changes, it will cause a large amount of data to be re-downloaded multiple files.

Stateless feature — huge HTTP headers

Stateless means that the protocol has no memory capacity for the connection status. Pure HTTP does not have mechanisms such as cookies. Every connection is a new connection.

Header often carries many fixed header fields such as “User Agent”, “Cookie”, “Accept”, “Server”, etc. (as shown below), up to hundreds or even thousands of bytes. However, Body often only has a few dozen bytes (such as GET requests, 204/301/304 responses), becoming a genuine “big head”. The content carried in the Header is too big, which increases the cost of transmission to some extent. More fatally, many field values in the response message are repeated, which is a waste.

Plaintext transmission — insecurity

When HTTP/1.1 transmits data, all transmitted content is plaintext, and neither the client nor the server can verify each other’s identity, which can’t ensure data security to some extent.

Not support server push messages

Introduction to SPDY and HTTP/2

SPDY protocol

As we mentioned above, due to the defects of HTTP/1.x, we will introduce sprite images, inline small images, use multiple domain names, etc., to improve performance. However, these optimizations bypass the protocol. Until 2009, Google announced the SPDY protocol it developed to mainly resolve the inefficiency of HTTP/1.1. Google released SPDY, which can be considered as officially restructuring the HTTP protocol itself. Lower latency, compress headers, etc., the practice of SPDY has proved the effect of these optimizations, and finally led to the birth of HTTP/2.

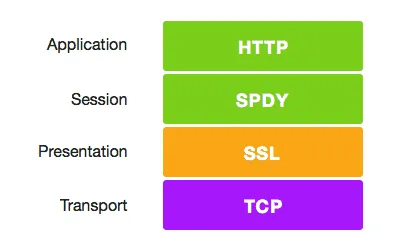

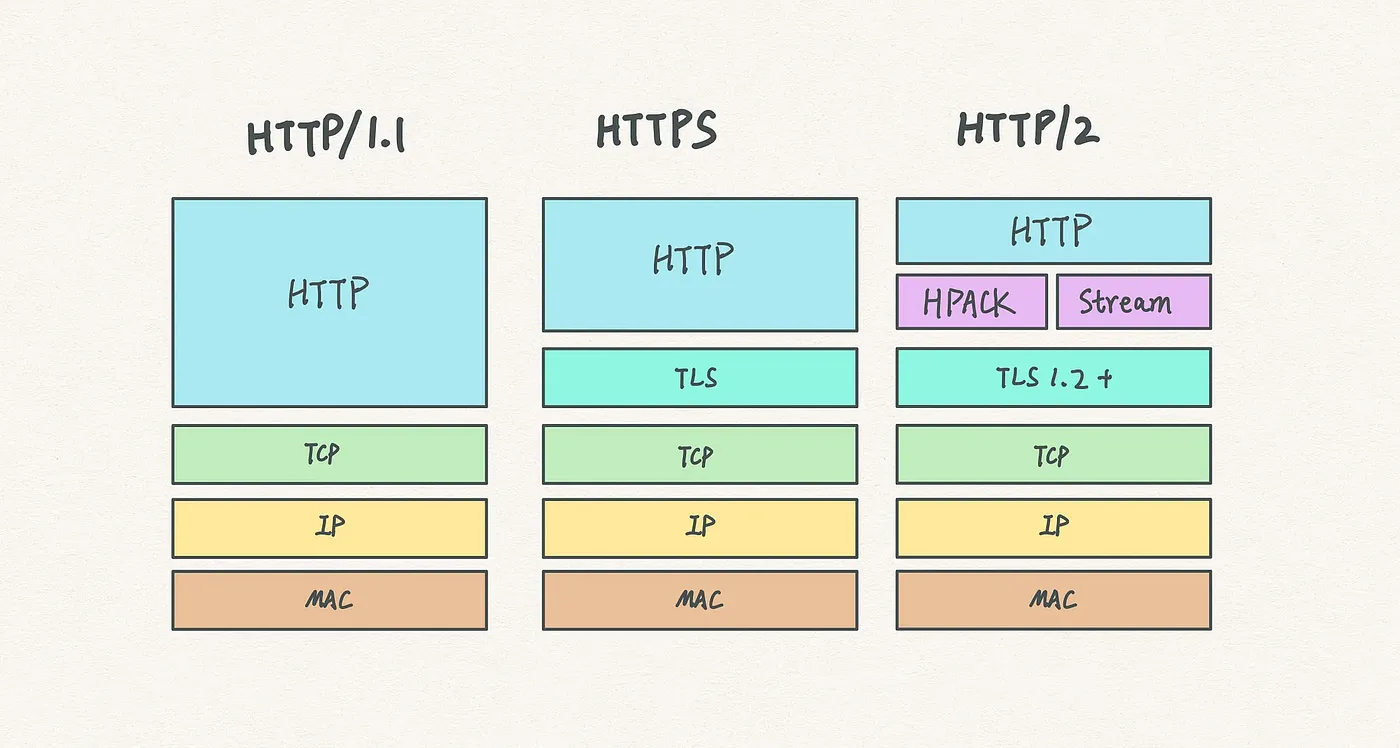

HTTP/1.1 has two main drawbacks: insecurity and low performance. Because it bears the huge historical burden of HTTP/1.x, compatibility is the primary goal when modifying the protocol, otherwise it will damage countless existing assets on the internet. As shown above, SPDY is located below HTTP and above TCP and SSL, which means it can easily be compatible with older versions of the HTTP protocol (encapsulating the content of HTTP1.x into a new frame format) and can use existing SSL functions.

After the SPDY protocol was proven feasible on the Chrome browser, it was used as the basis for HTTP/2, and its main features were inherited in HTTP/2.

Introduction to HTTP/2

In 2015, HTTP/2 was released. HTTP/2 is a substitute for the existing HTTP protocol (HTTP/1.x), but it is not a rewrite, HTTP methods/status codes/semantics are the same as HTTP/1.x. HTTP/2 is based on SPDY, focusing on performance, with the main goal of using only one connection between the user and the website. From the current situation, some top-ranking sites at home and abroad have basically implemented the deployment of HTTP/2, and using HTTP/2 can bring an efficiency improvement of 20% to 60%.

HTTP/2 consists of two specifications:

Hypertext Transfer Protocol version 2 — RFC7540

HPACK — Header Compression for HTTP/2 — RFC7541

New Features of HTTP/2

Binary Transmission

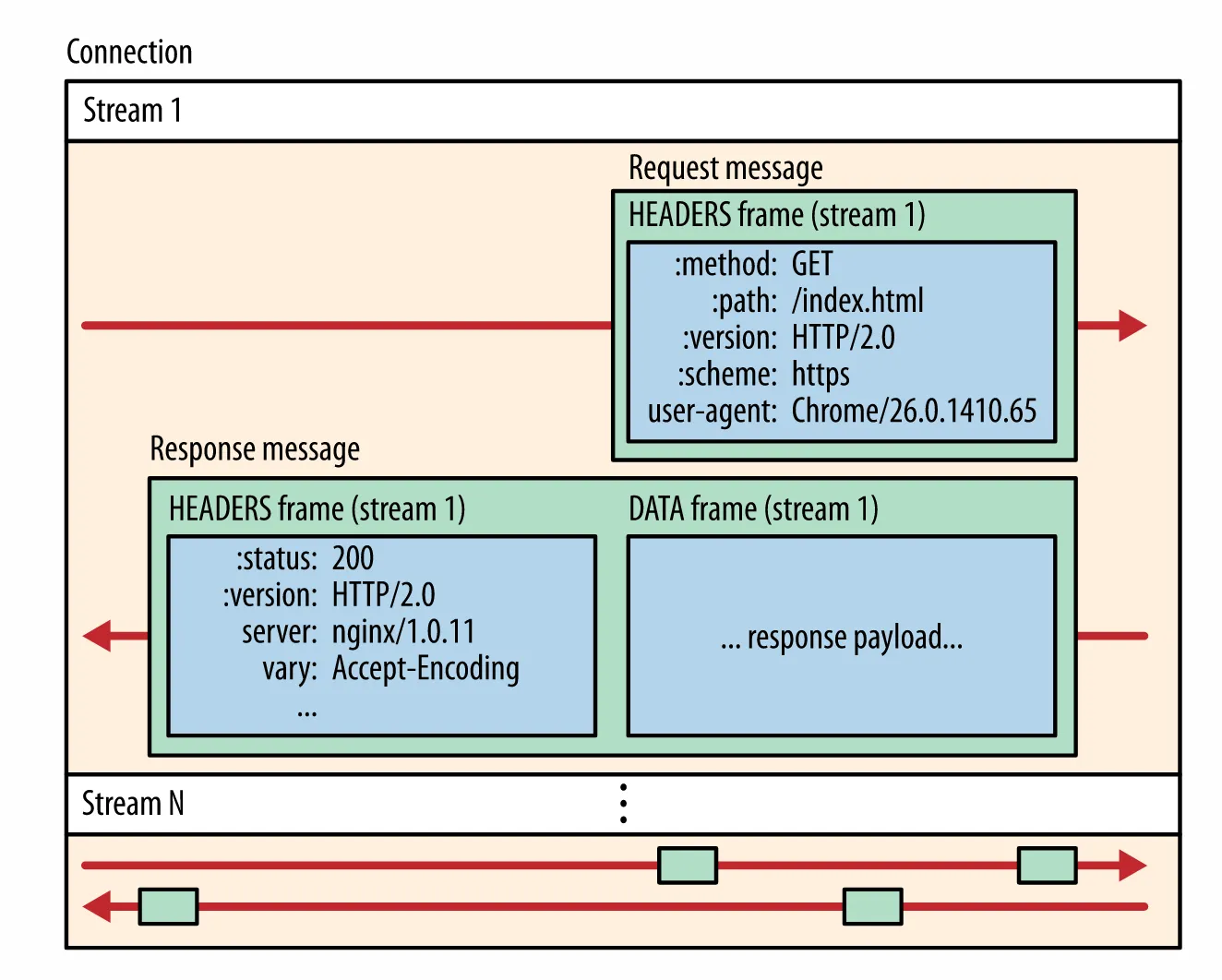

The great reduction in data transmission of HTTP/2 is mainly due to two reasons: binary transmission and Header compression. Here we first introduce binary transmission, HTTP/2 transmits data in binary format, rather than the text-based messages in HTTP/1.x, making binary protocol parsing more efficient. HTTP/2 splits request and response data into smaller frames, and they are encoded in binary.

It moves part of the TCP protocol feature to the application layer, and “breaks up” the original “Header+Body” message into several small binary “frames”, using the “HEADERS” frame to store header data and the “DATA” frame to store entity data. After HTP/2 data is frame-split, the message structure of “Header+Body” completely disappeared, and the protocol only sees one “fragment” after another.

In HTTP/2, all communications under the same domain name are completed on a single connection, which can carry an arbitrary number of bidirectional data streams. Each data stream is sent in the form of messages, and messages are composed of one or more frames. Multiple frames can be sent out of order, and can be reassembled based on the stream identifier in the frame header.

Header Compression

HTTP/2 did not use traditional compression algorithms, but developed a dedicated “HPACK” algorithm. It establishes a “dictionary” at both the client and server ends, uses index numbers to represent repetitive strings, and uses Huffman coding to compress integers and strings, which can reach a high compression rate of 50%~90%.

In detail:

The client and server use a “header table” to track and store previously sent key-value pairs. For the same data, it no longer is sent with each request and response;

The header table always exists during the survivability of the HTTP/2 connection and is gradually updated by the client and server together;

Each new header key-value pair is either appended to the end of the current table or replaces the value previously in the table.

For example, in the two requests in the following image, Request 1 sends all header fields, and the second request only needs to send difference data. In this way, redundant data is reduced and overhead is lowered.

Multiplexing

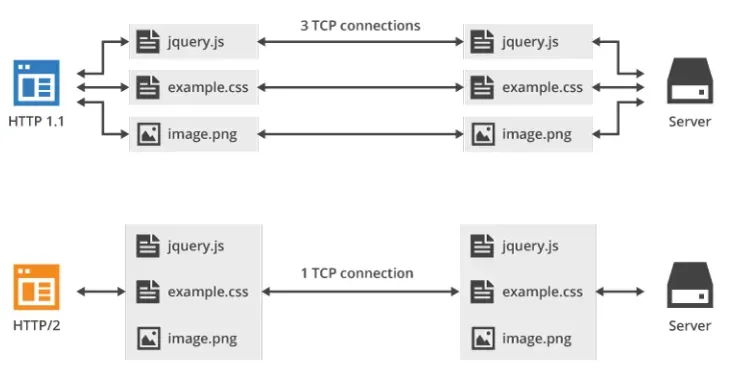

Multiplexing technology was introduced in HTTP/2. Multiplexing effectively solves the problem of browsers limiting the number of requests under the same domain name, and it is also easier to achieve full-speed transmission, because opening a new TCP connection requires gradually increasing the transmission speed.

In HTTP/2, after binary framing, HTTP/2 no longer relies on TCP connections to implement multi-stream parallelism. In HTTP/2:

All communications under the same domain name are completed on a single connection.

A single connection can carry an arbitrary number of bidirectional data streams.

Data streams are sent in the form of messages, and messages are composed of one or more frames. Multiple frames can be sent out of order, as they can be reassembled based on the stream identifier in the frame header.

This feature greatly improves performance:

A single domain name only needs to occupy one TCP connection, use one connection to send multiple requests and responses in parallel. In this way, the download process of the entire page resource only needs one slow start, and at the same time, it avoids the problems caused by multiple TCP connections competing for bandwidth.

Multiple requests/responses are sent in parallel overlap, and they do not affect each other.

In HTTP/2, each request can carry a 31-bit priority value, 0 indicates the highest priority, and the larger the value, the lower the priority. With this priority value, clients and servers can adopt different strategies when processing different streams, to send streams, messages, and frames in the most optimal way.

As shown above, the technology of multiplexing can transmit all request data through just one TCP connection.

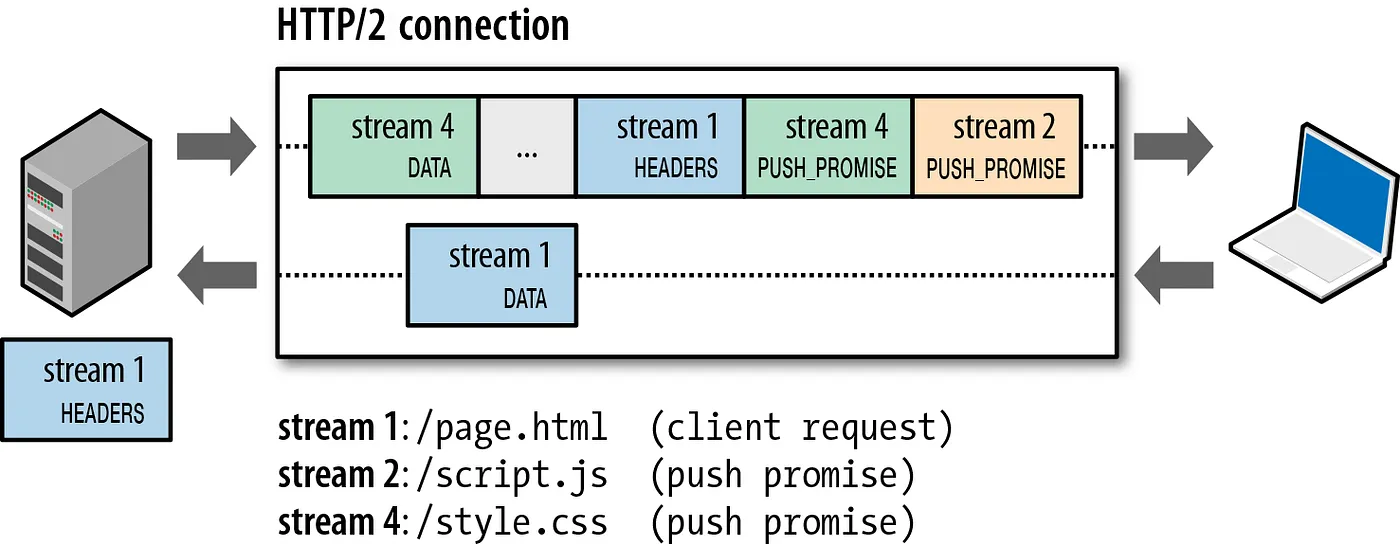

Server Push

HTTP2 has to some extent changed the traditional “request-response” working mode. The server is no longer completely passively responding to requests, but can also actively send messages to the client by creating new “streams”. For instance, when the browser just requests HTML, the server may proactively send JS and CSS files that might be used to the client, reducing waiting latency. This is known as “server push” (also called Cache push).

For example, as shown in the figure below, the server actively pushes JS and CSS files to the client, without the need for the client to send these requests when parsing HTML.

Furthermore, it should be noted that while the server can actively push, the client has the right to choose whether to accept it or not. If the resources pushed by the server have already been cached by the browser, the browser can refuse to accept them by sending an RST_STREAM frame. Active pushing also complies with the same-origin policy, in other words, the server cannot arbitrarily push third-party resources to the client, but must be confirmed by both parties.

Enhanced Security

For the consideration of compatibility, HTTP/2 continues the “plaintext” feature of HTTP/1 and can use plaintext to transmit data as before. It doesn’t force the use of encrypted communication; however, the format is still binary, just no decryption is required.

But since HTTPS has become the trend, and mainstream browsers such as Chrome and Firefox have publicly announced that they only support the encrypted HTTP/2, so the “de facto” HTTP/2 is encrypted. That is to say, the HTTP/2 that can usually be seen on the Internet all uses the “https” protocol name and runs on TLS. The HTTP/2 protocol defines two string identifiers: “h2” represents encrypted HTTP/2, and “h2c” represents plaintext HTTP/2.

Drawbacks of HTTP/2

Although HTTP/2 solves many problems of the previous versions, it still has a huge problem, mainly caused by the underlying TCP protocol that it relies on. The main drawbacks of HTTP/2 are as follows:

Delay in establishing TCP and TCP+TLS connections

Head-of-line blocking in TCP not completely solved

Server load increase due to multiplexing

Multiplexing more prone to timeout

Connection establishment delay

HTTP/2 uses the TCP protocol for transmission, and if HTTPS is used, the TLS protocol is required for secure transmission. And using TLS also requires a handshake process, which means there are two handshake delay processes:

① When establishing a TCP connection, a three-way handshake with the server is needed to confirm the connection is successful, that is, only after 1.5 RTTs can data transmission proceed.

② When establishing a TLS connection, there are two versions of TLS — TLS1.2 and TLS1.3, each with different connection establishment times, roughly requiring 1~2 RTTs.

In summary, before transmitting data, we have to spend 3~4 RTTs.

RTT (Round-Trip Time):

The round-trip time. This is the total delay from the time the sender starts sending data until the sender receives confirmation from the receiver (the receiver immediately sends confirmation after receiving the data).

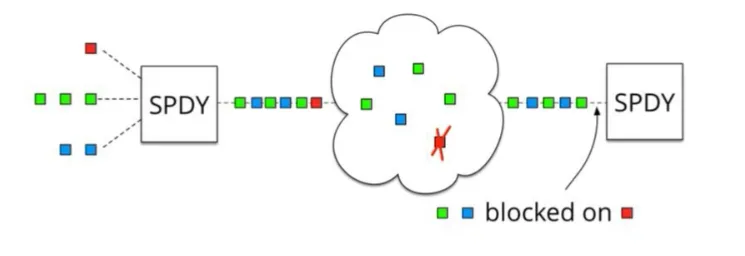

TCP Head-of-line blocking not completely solved

As we mentioned earlier, multiple requests in HTTP/2 are within one TCP pipe. However, when packet loss occurs, HTTP/2’s performance is actually worse than HTTP/1. Because TCP has a special “packet loss retransmission” mechanism to ensure reliable transmission, the lost packet has to wait for retransmission confirmation. When HTTP/2 experiences packet loss, the entire TCP has to start waiting for retransmission, which will block all requests in that TCP connection (as shown in the figure below). For HTTP/1.1, multiple TCP connections can be opened, so such a situation would only affect one of the connections, and the remaining TCP connections can still transmit data normally.

RTO: The full English name is Retransmission TimeOut, which is the retransmission timeout time. RTO is a dynamic value and will change with the network. RTO is calculated based on the round-trip time RTT of a given connection. The ack returned by the receiver is the sequence number of the next group of packets the receiver hopes to receive.

Some might wonder why not directly modify the TCP protocol? In fact, this has become an impossible task. The existence time of TCP is too long, it is already prevalent in various devices, and this protocol is implemented by the operating system, making it unrealistic to update.

Server Stress Increase due to Multiplexing

Multiplexing does not limit the number of simultaneous requests. The average number of requests is the same as usual, but there will be many brief bursts of requests, leading to a sudden surge in instantaneous QPS (queries per second).

Multiplexing more prone to Timeout

A large number of requests are sent at the same time. Since there are multiple parallel streams within the HTTP2 connection, and the network bandwidth and server resources are limited, the resources of each stream will be diluted. Although their start times are closer, they may all timeout.

Even using a load balancer like Nginx, it might be tricky to correctly do throttling. Secondly, even if you introduce or adjust the queuing mechanism to the application, the number of connections that can be handled at once is still limited. If requests are queued, you also need to pay attention to discarding requests after the response times out, to avoid wasting unnecessary resources. Reference

HTTP/3 New Features

Introduction to HTTP/3

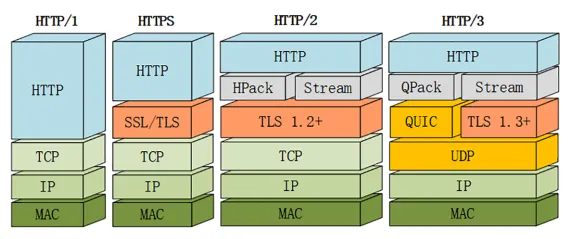

Google realized these problems when promoting SPDY, so they started up a new oven and created a “QUIC” protocol based on the UDP protocol, allowing HTTP to run on QUIC instead of TCP. This “HTTP over QUIC” is the next major version of the HTTP protocol, HTTP/3. It has achieved a qualitative leap based on HTTP/2 and truly “perfectly” solved the “head-of-line blocking” problem.

Although QUIC is based on UDP, a number of functionalities have been added on top of the original foundation. We will focus on several new QUIC features next. However, HTTP/3 is still at a draft stage at the moment, there may be changes before its official release, so this article will avoid unstable details as much as possible.

New Features of QUIC

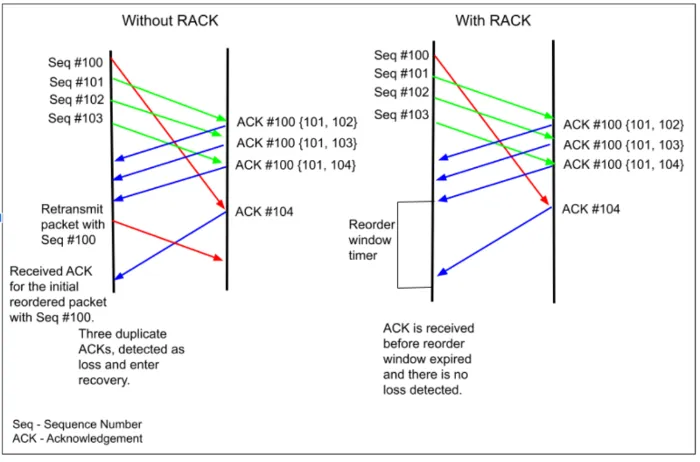

As mentioned earlier, QUIC is based on UDP, which is “connectionless” and doesn’t need “handshakes” and “waves”, making it faster than TCP. In addition, QUIC implements reliable transmission, ensuring that data can indeed reach its destination. It also introduced “streams” and “multiplexing” similar to HTTP/2. A single “stream” is ordered and may block due to packet loss, but other “streams” will not be affected. To be more specific, the QUIC protocol has the following features:

Achieved similar features to TCP such as flow control and transmission reliability

Although UDP does not provide reliable transmission, QUIC adds a layer on top of UDP to ensure reliable data transmission. It offers packet retransmission, congestion control, and other features found in TCP.

Where does the QUIC protocol improve? Mainly in the following aspects:

Pluggable: Different congestion control algorithms can be implemented at the application level.

Monotonically increasing Packet Number: Packet Number is used instead of TCP’s seq.

No Reneging: As long as a Packet is Acked, it is assumed that it has been received correctly.

Forward Error Correction (FEC).

More Ack blocks and increased Ack Delay time.

Traffic control at the stream and connection level.

Implemented Quick Handshake Feature

Since QUIC is based on UDP, QUIC offers the use of 0-RTT or 1-RTT to establish a connection, which means QUIC can transmit and receive data at the fastest speed, greatly improving the speed of opening a webpage for the first time. It can be said that 0RTT connection setup is the biggest performance advantage of QUIC compared to HTTP2.

Integrated TLS encryption feature

Currently, QUIC uses TLS1.3, which offers more advantages compared to its predecessors, the most important of which is reducing the number of RTTs spent on handshakes.

In a complete handshake, 1-RTT is required to establish a connection. TLS 1.3 session recovery can directly send encrypted application data, not requiring extra TLS handshake, that is, 0-RTT.

However, TLS1.3 is not perfect. TLS 1.3’s 0-RTT cannot guarantee Forward Secrecy. Simply put, if an attacker somehow obtains the Session Ticket Key, they can decrypt the previous encrypted data.

To alleviate this problem, we can set the DH static parameters corresponding to Session Ticket Key to expire in a short time (usually a few hours).

Multiplexing, completely solving the problem of head-of-line blocking in TCP

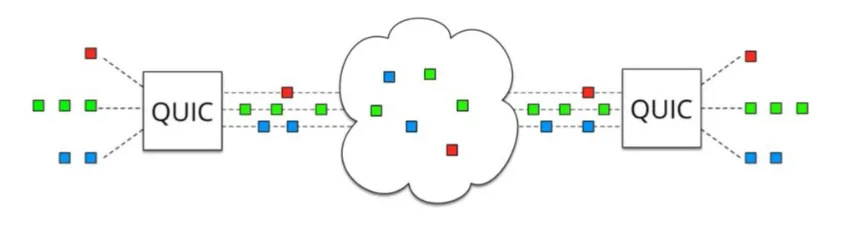

Unlike TCP, QUIC achieves multiple independent logical data streams on the same physical connection (as shown below). By realizing independent data stream transmission, the head-of-line blocking problem in TCP is solved.

Connection migration

TCP uses 4 factors (client IP, port, server IP, port) to affirm a connection. But QUIC lets the client generate a Connection ID (64 bits) to distinguish different connections. As long as the Connection ID remains the same, the connection does not need to be reestablished, even if the client’s network changes. As the migrating client continues to use the same session key to encrypt and decrypt packets, QUIC also provides automatic encryption verification for migrating clients.

Conclusion

HTTP/1.1 has two major drawbacks: lack of security and poor performance.

HTTP/2 is completely compatible with HTTP/1 and provides a “more secure HTTP and faster HTTPS”, binary transmission, header compression, multiplexing, server push, etc. These technologies fully utilize the bandwidth and reduce latency, greatly improving the online experience;

QUIC is implemented based on UDP and forms the underlying support protocol in HTTP/3, This protocol is based on UDP, and also benefits significantly from TCP, resulting in a fast and reliable protocol.

Interview question: The difference between http2 and http1.1, do you know about http3, please elaborate;