In JavaScript, the object type is one of the most important types and is often used for data processing in projects. Although we frequently use this type, its methods are not commonly used or are seldom used. Unnoticeably, the number of methods for JavaScript objects has reached 29. Today, let’s take a look at the use of these 29 methods.

Additionally, when using typeof on an Array, you’ll find that an array is a type of object, or you might say that an array is a special type of object. Therefore, most methods that apply to objects can also be used on arrays, and some effects might surprise you.

Object.defineProperty intercepts object properties

Anyone familiar with Vue should be quite acquainted with this method, as in Vue2, the underlying reactive interception is implemented using Object.defineProperty combined with the observer pattern. It’s worth mentioning this because the description object will be used in some methods later on.

The Object.defineProperty method accepts three parameters: the first is the target object, the second is the property to be added or modified, and the third is the description object. It returns the object passed in.

Attributes of the description object:

configurable: Whether it is configurable. Defaults to false. When false, the property cannot be configured.

enumerable: Whether it is enumerable. Defaults to false. When false, the property cannot be enumerated, meaning it cannot be found using the in operator, or during a for-in loop.

writable: Whether it is writable. Defaults to false. When false, the property cannot be modified.

value: The property value. Defaults to undefined. It can be any type of value in JavaScript.

get method: Returns value, which by default is undefined. This method is called when the property is accessed, and the property value obtained when accessed is the return value of this method.

set method: Default value is undefined. This method is called when the property is modified.

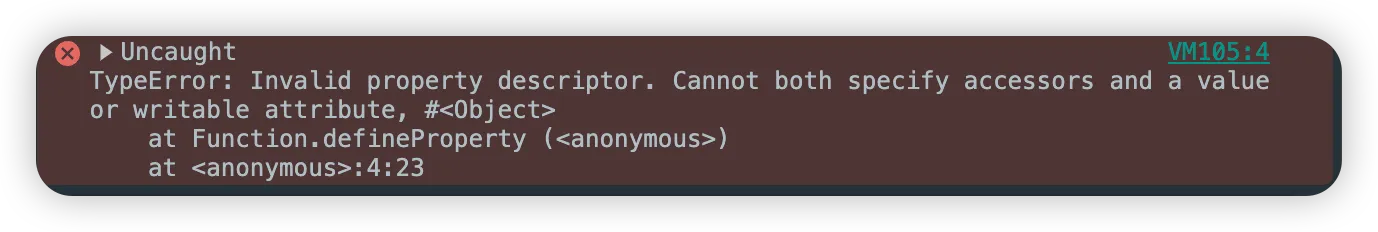

Note: When the configuration object includes the value and writable properties, it should not contain get and set methods, and vice versa. If the value property and get method exist at the same time, an error will occur.

Here’s an example in JavaScript:

| |

If you attempt to add get and set methods while also adding a value, it will cause an error.

| |

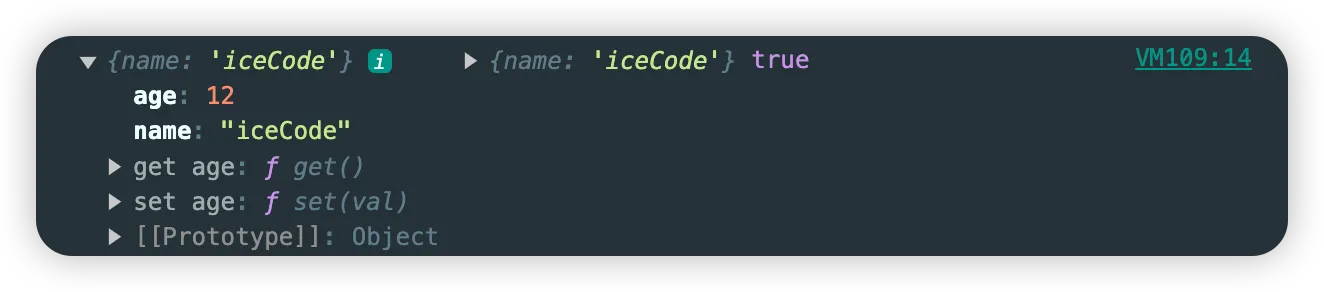

Using get and set to change object properties is something we might have seen in Vue projects. When printing the current data, you might find that the data shown in the console is not the latest, but when you expand it, it shows the latest data instead.

This is because objects in JavaScript are dynamic and can change at any time. When you use console.log to print an object, what you get is the state of the object at the moment of printing, not its real-time state. However, when you expand an object, you are actually retrieving all of the object’s property values again, so what you see is the latest state.

Here’s an example in JavaScript:

| |

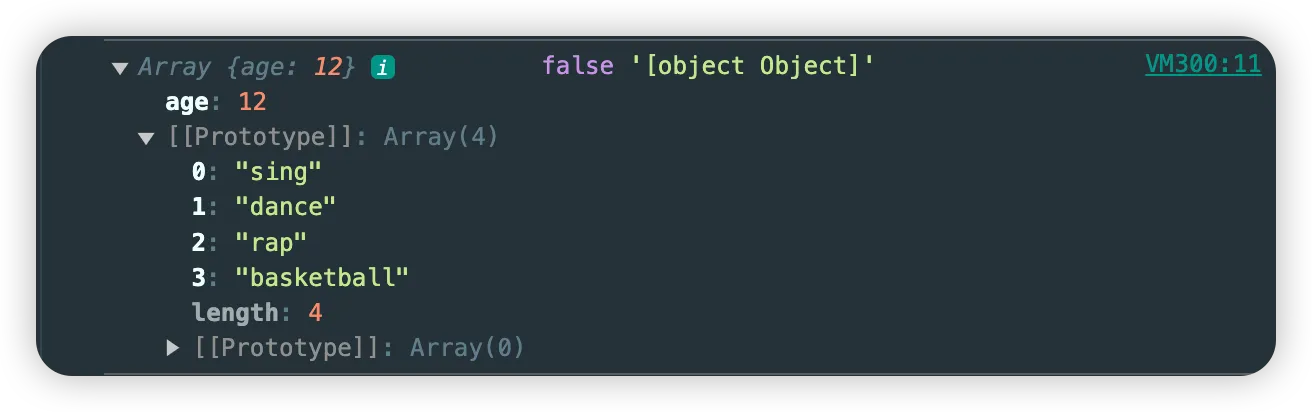

When the target object is an array, using Object.defineProperty works in a similar way as it does with objects. You can indeed add or modify properties on an array object, although this is not commonly seen or recommended for standard operations on arrays, since arrays are typically used for storing indexed elements rather than named properties.

Here’s your TypeScript example:

| |

Have you guessed the outcome? Seen this type before?

The result is that the array now has a new property named age with the value iceCode. This property is not an element of the array, but rather an additional property on the array object. So, if you did something like console.log(newObj.length), it would still be 0 because the age property does not count as an element of the array. However, accessing newObj.age would return iceCode.

This showcases JavaScript’s flexibility with objects and its prototype-based nature, where both arrays and plain objects derive from Object, allowing the addition of properties in a similar manner. However, adding non-index properties to an array is usually not recommended because it can lead to unexpected behavior and confusion, as the primary use-case for arrays is to handle indexed collections.

In the context of the given TypeScript code where an array has been modified using Object.defineProperty to include a custom property, the underlying type of newObj remains an array. However, due to the dynamic and flexible nature of JavaScript (and by extension, TypeScript), arrays are special kinds of objects that can also have properties assigned to them beyond their indexed elements.

To access the values within newObj, you would use standard property access methods depending on what you’re trying to retrieve:

Index-based access for array elements (e.g.,

newObj[0]).Dot notation or bracket notation for accessing custom properties (e.g.,

newObj.ageornewObj['age']).

Here’s how you would analyze newObj:

| |

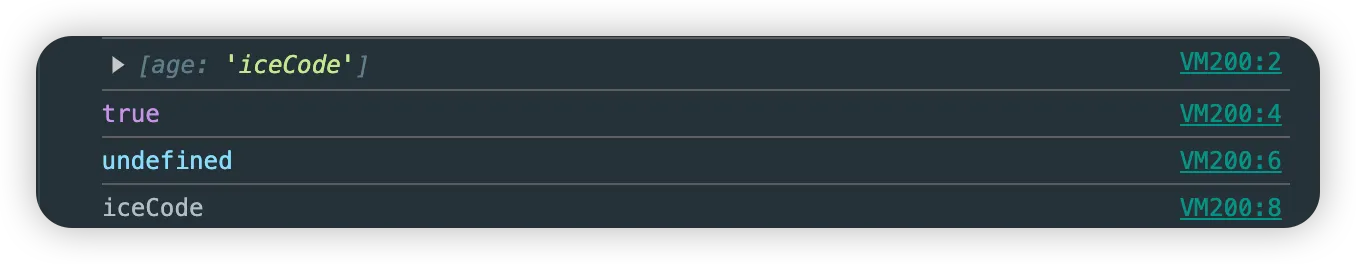

Given that newObj is the result of calling Object.defineProperty on an empty array and adding an age property:

console.log(newObj);would output the array along with the custom age property. However, the way custom properties are displayed might differ based on the environment (e.g., Node.js, browser dev tools, etc.).console.log(Array.isArray(newObj));would log true, indicating thatnewObjis still considered an array.console.log(newObj[0]);would logundefinedbecause no elements have been added to the array itself; it remains empty.console.log(newObj.age);would logiceCode, as that’s the value assigned to the age property.

This example illustrates JavaScript’s versatility, where arrays are particular kinds of objects and hence can have additional properties set on them, despite primarily being used for ordered collections of items.

When you add a custom property to an array and make it enumerable by setting enumerable: true, you can indeed see different behaviors with different iteration methods in JavaScript (or TypeScript). Here’s how each method interacts with the newObj that is essentially an array with an additional custom property:

1. for…of Loop

The for…of loop iterates over iterable objects (including arrays, Map, Set, arguments object, etc.) and accesses their values. It does not iterate over object properties.

| |

Result: This will print "222", "for of" to the console. It will not access the age property because for...of iterates over array elements (values), not object properties.

2. forEach Method

The .forEach() method executes a provided function once for each array element. Like for...of, it operates on array elements and does not iterate over additional object properties.

| |

Result: This will print "222", "forEach" to the console. The forEach method ignores the age property and only operates on the array’s elements.

3. for…in Loop

The for...in loop iterates over all enumerable properties of an object, including inherited enumerable properties. This is where you’ll see a difference regarding the custom property.

| |

Result: This will print:

"0", "222", "for in"for the array element"age", "iceCode", "for in"for the custom property

Here, the for...in loop iterates over both the array index (as a string) and the custom age property because it includes all enumerable properties, not just those that are array indices.

So, when you have a modified array with an additional custom, enumerable property, both traditional array elements and the custom property are accessed using a for...in loop, while the for...of loop and .forEach() method focus on the array elements only.

Using Object.defineProperty to add an object to an array can produce a jaw-dropping effect. However, this added object is in a unique position. Even though it is in the array, access to or iteration over it must be done using object manipulation.

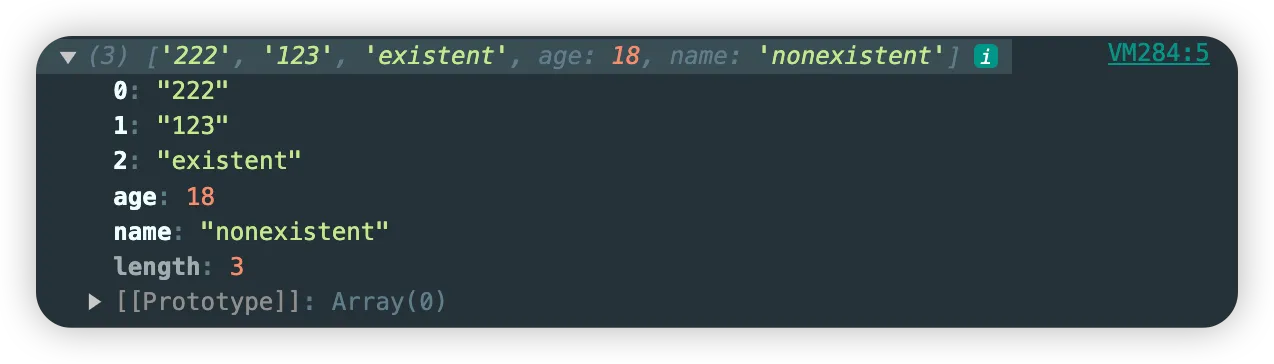

What happens, then, if we add or modify elements in this array, or change elements using property names?

| |

The final outcome is that these operations do not interfere with each other. Property values can be changed, non-existent properties can be added, and elements added using push exist independently as indexed elements.

Object.defineProperties intercepts object

The Object.defineProperties method can be considered a strengthened version of Object.defineProperty. While Object.defineProperty can only configure one property at a time, Object.defineProperties allows for the hijacking of multiple properties simultaneously. Object.defineProperties accepts two parameters: the target object and an object that specifies properties to be hijacked. Each key in the second object represents a property to be hijacked, with the value being the configuration object for that property. It returns the target object.

| |

If the target object is an array, the process and the operations of obtaining, modifying, and adding values are the same as with Object.defineProperty.

Object.assign for Shallow Copying Objects

Object.assign performs a shallow copy on objects. It takes two or more arguments, where the first argument is the target object, and the subsequent arguments are the objects to be copied. It returns the target object itself. The term “shallow copy” refers to copying the properties of the objects to be copied onto the target object.

| |

If the target object is an array… Yes, the type is Array.

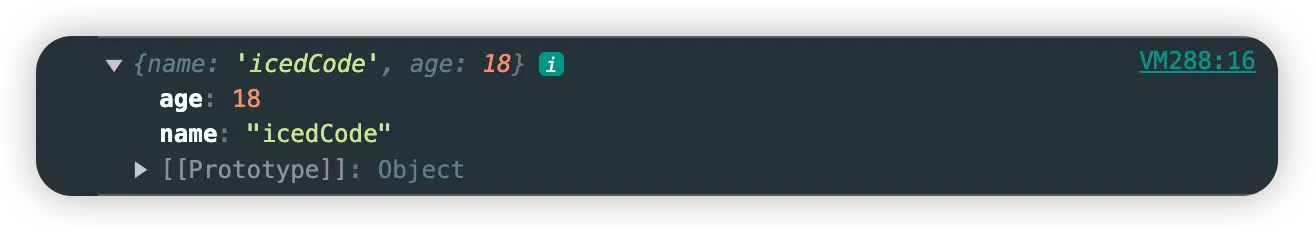

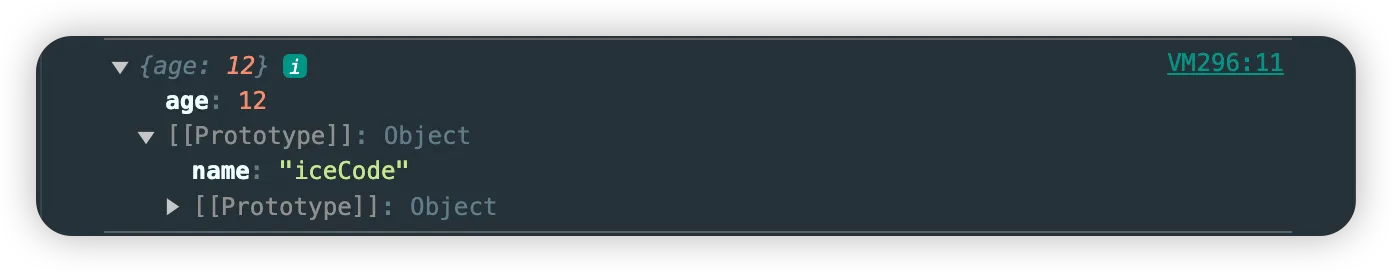

Object.create uses an existing object as a prototype to create a new object

Object.create creates a new object, taking two arguments: the prototype object for the new object, and the second argument is the same as the second argument for Object.defineProperties, which contains properties and values for the new object itself.

| |

If the first argument is an array, then the prototype of the new object will be an array.

| |

Object.freeze Freezes Objects

The Object.freeze method freezes an object, making the target object non-configurable (no modifications allowed through methods such as Object.defineProperty), non-extensible, non-deletable, and immutable (including changes to the prototype). It takes an object to be frozen and returns that object. Note: Once an object is frozen, this operation is irreversible, and the object cannot be unfrozen.

| |

Object.isFrozen Determine if an Object is Frozen

Object.isFrozen checks whether an object is frozen; it returns true if frozen, otherwise false.

An empty non-extensible object is considered frozen.

A non-extensible object with properties that have been deleted is considered frozen.

A non-extensible object with properties set to non-configurable and non-writable (

configurable: false, writable: false) is considered frozen.A non-extensible object with an accessor property that is set to non-configurable and non-writable (

configurable: false, writable: false) is considered frozen.An object frozen with

Object.freezeis considered frozen.

| |

Object.seal Seals an Object

Object.seal seals an object, and compared to Object.freeze, it allows modifying the object’s existing properties but still prohibits deleting, adding, etc.

| |

Object.isSealed Determine if an Object is Sealed

Object.isSealed checks whether an object is sealed; it returns true if sealed, otherwise false. The criteria are largely similar to those mentioned above, and a frozen object is definitely considered sealed.

An empty non-extensible object is considered a sealed object.

A non-extensible object with properties that have been deleted is considered a sealed object.

A non-extensible object with properties set to non-configurable (

configurable: false) is considered sealed.A non-extensible object with an accessor property that is set to non-configurable (

configurable: false) is considered sealed.An object sealed with

Object.sealis considered a sealed object.An object frozen with

Object.freezeis considered a sealed object.

| |

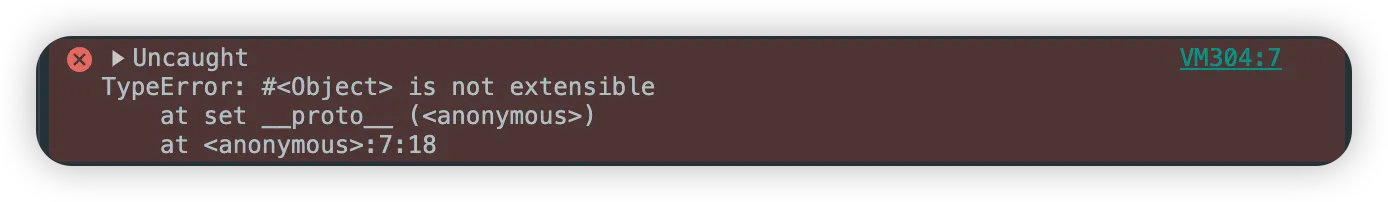

Object.preventExtensions Prevent Object Extensions

Object.preventExtensions prohibits the extension of an object. Apart from not being able to add new properties, other operations are permitted, including that the prototype cannot be reassigned.

| |

Object.isExtensible Determine if an Object is Extensible

Object.isExtensible checks whether an object is extensible and returns a boolean value. By default, regular objects are extensible, so the result will be true, whereas non-extensible objects will return false.

Objects that are frozen are not extensible.

Objects that are sealed are not extensible.

Objects marked as non-extensible are not extensible.

| |

Additionally: The methods for freezing, sealing, and preventing extensions are also applicable to arrays, making it impossible to add new properties or make certain modifications. These are not demonstrated here.

Object.fromEntries Convert a List of Key-Value Pairs into an Object

Object.fromEntries transforms a list in key-value pair format into an object, such as data from a Map or two-dimensional array data.

| |

Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty Check if an Object Owns a Property

Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty is a prototype method that allows an object instance to check whether it has a specific property, returning a boolean value. If the property exists on the object itself, it returns true. If it does not exist or exists only on the prototype, it returns false.

| |

Object.hasOwn Check if an Object Owns a Property

Object.hasOwn serves as a replacement for Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty, intended to be used in its place. It accepts two parameters: the target object and the property value to search for. It returns a boolean value, with the result being the same as that of Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.

| |

Object.getOwnPropertyNames Returns an array containing the own properties of an object, including non-enumerable ones

Object.getOwnPropertyNames takes a target object and returns an array containing its own properties, including non-enumerable properties, but does not include Symbol properties.

| |

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols Returns an array containing the Symbol properties of an object

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols takes a target object and returns an array, which includes only the Symbol properties of the target object.

| |

Object.getPrototypeOf Obtains the prototype of an object

Object.getPrototypeOf retrieves the prototype of the target object, taking one parameter and returning the prototype object of that target object.

| |

Object.setPrototypeOf Modifies the prototype of an object

Object.setPrototypeOf changes the prototype of the target object, taking two parameters, the first being the target object and the second the prototype object to be set. This method is not recommended for use as modifying the prototype using this method is very slow. It is suggested to use Object.create to create a new object instead.

| |

Object.prototype.isPrototypeOf: Determines whether an object exists on another object’s prototype

As a prototype method of Object, it is generally used on constructors. However, regular objects can also use it, and similarly, this method is not protected. It takes a target object and returns a boolean value.

| |

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor Obtains the descriptor object of an object’s own property

The Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor method retrieves the descriptor object of an object’s own property, taking two parameters, the first being the target object and the second the property name, returning a descriptor object for that property. It is noted that modifying the returned descriptor object’s value does not change the original property’s value.

| |

Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors Retrieves descriptor objects for all own properties of an object

The Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptors method obtains the descriptor objects for all the own properties of an object, taking one parameter, which is the target object, and returns a descriptor object for each of the object’s own properties. As mentioned earlier, modifying the values of the returned descriptor objects does not change the values of the original properties.

| |

Object.prototype.propertyIsEnumerable Indicates whether a specified property is enumerable

The Object.prototype.propertyIsEnumerable prototype method signifies whether a specified property is enumerable. It takes a parameter specifying the property and returns a boolean value.

| |

Object.keys Returns an array of an object’s own enumerable properties

Object.keys takes a target object and returns an array of the object’s own enumerable properties. This means properties configured as non-enumerable or those that are Symbol properties cannot be found.

| |

Object.values Returns an array of an object’s own enumerable property values

Object.values takes a target object and returns an array containing the values of the object’s own enumerable properties. This means values of properties configured as non-enumerable or those that are Symbol properties cannot be accessed.

| |

Object.entries Returns an array of an object’s own enumerable properties and their values as a two-dimensional array

Object.entries takes a target object and returns a two-dimensional array containing the enumerable properties and their values of the object. Properties configured as non-enumerable or Symbol properties cannot have their values retrieved.

| |

Object.is Compares whether two values are the same

Object.is compares two values for equality, offering more accuracy than comparison operators. It accepts two arguments, the first and second values to compare, and returns a boolean indicating the result of the comparison.

| |

The Object.is method can be very useful in several scenarios, particularly when you need to perform precise equality checks. Here are some situations where it comes in handy:

Comparing Edge Values:

Object.isexcels at comparing values that are tricky with the == or === operators, such as NaN. While NaN === NaN evaluates to false,Object.is(NaN, NaN)returns true, making it invaluable for checking these types of values.Detecting Signed Zeros:

Object.iscan differentiate between -0 and +0, which is something equality operators (==, ===) cannot do. This can be important in mathematical computations where the sign of zero can affect the outcome.Immutable and Functional Programming: In environments or programming paradigms that rely heavily on immutability (like React or Redux in JavaScript),

Object.isprovides a reliable way to detect changes or verify if two objects or values are exactly the same, which is crucial for optimizing rendering or reducing unnecessary calculations.Strict Equality Checks: When you need to enforce strict equality without type coercion,

Object.isoffers a more stringent solution than ===. It’s especially useful in scenarios where the exact nature of the values being compared is critical to the logic of your application.Debugging and Testing:

Object.iscan be particularly useful in testing frameworks or during debugging sessions when determining the exact state or value of an object is necessary for diagnosing issues

In essence, Object.is is a powerful tool for scenarios requiring precise and nuanced comparisons, significantly when dealing with JavaScript’s quirks and edge cases.

valueOf toString toLocaleString

The methods valueOf, toString, and toLocaleString are all methods on the Object prototype. Essentially, they hold no significant meaning on the Object itself. The valueOf method is intended to be overridden by derived objects to implement custom type conversion logic. The toString method is aimed to be overridden (customized) by derived class objects for type conversion logic. The toLocaleString method is intended to be overridden by derived objects to achieve specific purposes related to the locale.

In JavaScript, all types (excluding null) inherit from the Object’s prototype, meaning all types have these three derived methods. However, these methods have already been overridden to have their unique effects for different types. It is only necessary to understand that on the Object itself, these three methods essentially have no special effect.

Object.groupBy allows grouping elements within a given iterable object

The Object.groupBy method accepts two arguments. The first is the iterable object (like an Array) for grouping elements, and the second is a callback function that takes two arguments: the current element being iterated and the current iteration index. The returned object has separate properties for each group containing arrays of elements in that group.

| |

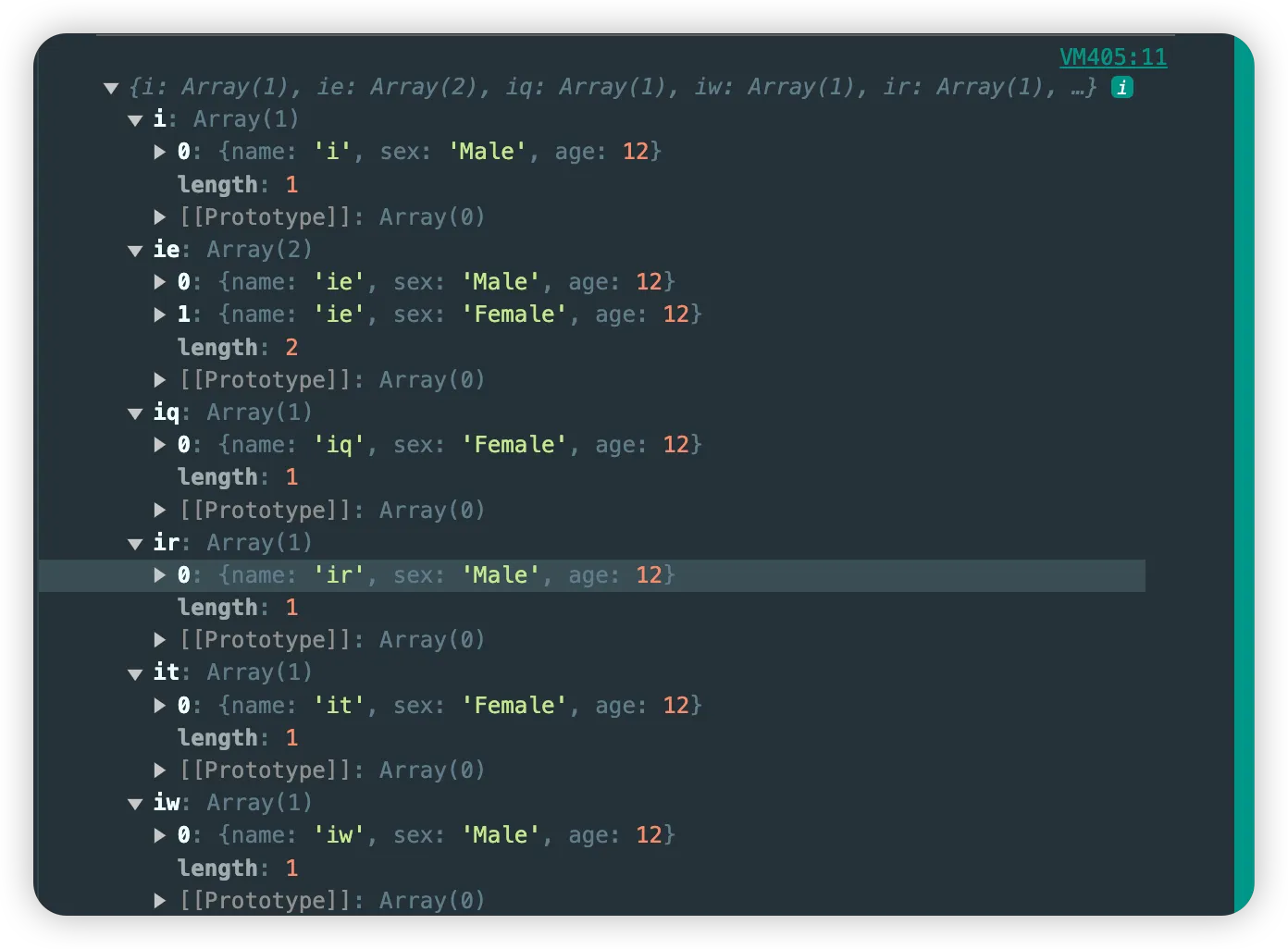

The property returned by the second callback of the Object.groupBy method determines the grouping criterion. For instance, if it returns v.name, the result would be as follows:

The Object.groupBy method can be particularly useful in several scenarios, such as:

Data Analysis and Reporting: When dealing with a large set of data, you can use

Object.groupByto categorize data into groups based on specific attributes, making it easier to analyze trends and patterns.Organizing User Interface Elements: In applications with complex user interfaces, grouping objects based on their properties can help in dynamically organizing UI elements, like categorizing contacts by their first letter or grouping messages by sender.

Enhancing Data Processing Efficiency: By grouping objects with common properties, algorithms can process each group separately, potentially improving the efficiency of data processing tasks.

Simplifying Data Aggregation: When you need to perform aggregate operations, such as counting, summing, or averaging values within categories, grouping data first can simplify the process.

Building Hierarchical Structures:

Object.groupBycan be instrumental in constructing hierarchical or tree-like data structures from flat data collections, based on shared characteristics or relationships

In essence, Object.groupBy shines in scenarios where organizing data into meaningful groups or categories can significantly improve readability, manageability, and processing efficiency.