Outline:

Distinguishing between process and thread

The browser is multi-process

What processes does a browser include?

Benefits of multi-process browsing

The focus is on the browser kernel (rendering process)

The communication process between the Browser process and the browser kernel (Renderer process)

- Sorting out the relationship between threads in the browser kernel

GUI rendering thread and JS engine thread are mutually exclusive

JS blocking page loading

WebWorker, is that JavaScript’s multi-threading?

WebWorker and SharedWorker

- Briefly comb through the browser rendering process

The sequence of load events and DOMContentLoaded events

Does the loading of CSS block the rendering of DOM tree?

Ordinary layers and composite layers

- Discussing JavaScript’s runtime mechanism from the Event Loop

Further supplement to the event loop mechanism

Talking separately about the timer

setTimeout rather than setInterval

Advanced event loop: macrotask and microtask

Summary

Distinguishing between process and thread

It’s quite normal for beginners to confuse threads and processes. Don’t worry about that. Let’s take a look at the following vivid metaphor:

A process is like a factory, which has its independent resources

Factories are independent from each other

A thread is like a worker in the factory, multiple workers cooperate to complete tasks

There is one or more workers within a factory

Workers share space with each other

Let’s further refine the concept:

Factory resources -> Memory allocated by the system (an independent block of memory)

Factories being independent -> Processes being independent from each other

Multiple workers cooperate to complete tasks -> Multiple threads within a process cooperate to complete tasks

There is one or more workers within a factory -> A process is composed of one or more threads

Workers share work space -> Threads within the same process share the program’s memory space (including code segments, data sets, heap, etc.)

Then, let’s reinforce this:

On a Windows computer, you can open the task manager and see a list of background processes. Yes, that’s where you can view the processes, and you can also see the memory resources and CPU occupancy rate of each process.

So, it should be easier to understand now: a process is the smallest unit of CPU resource allocation (the system will allocate memory to it)

Finally, let’s describe it again with more official terms:

A process is the smallest unit of CPU resource allocation (it is the smallest unit that can have resources and run separately)

A thread is the smallest unit of CPU scheduling (a thread is a unit of program execution based on a process, and there can be multiple threads in a process)

Tips

Different processes can communicate with each other, but the cost is high

Nowadays, the generally used terms: single-threaded and multi-threaded, both refer to single or multiple threads within one process. (So the core must belong to one process)

Browsers are multi-process

After understanding the difference between process and thread, let’s get to know a bit about browsers: (first, here’s a simplified understanding)

Browsers are multi-process

The reason why a browser can run is that the system allocates resources (CPU, memory) to its processes

To simplify it, every time you open a Tab, it’s like creating an independent browser process.

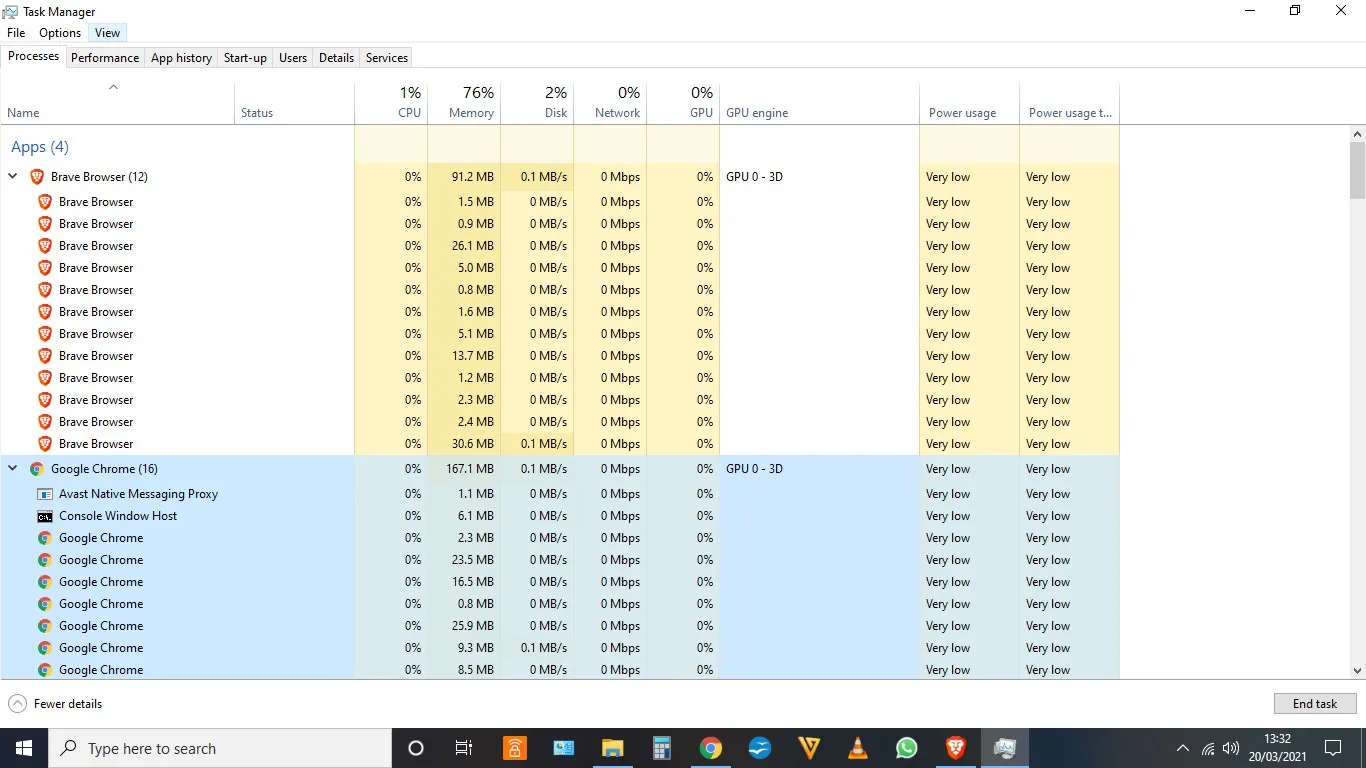

As for the above points, please check the first image:

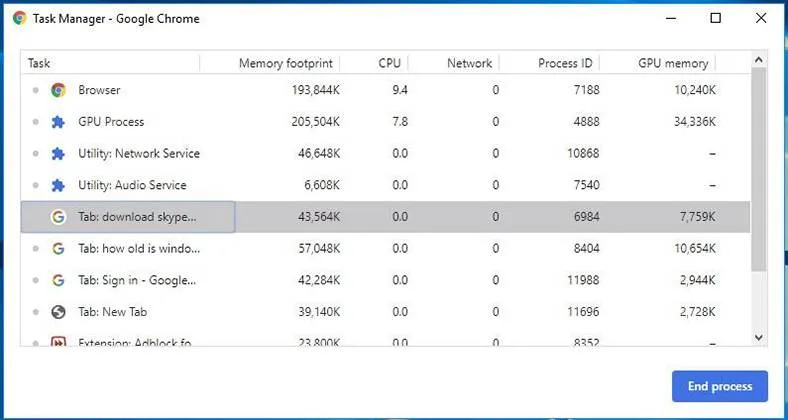

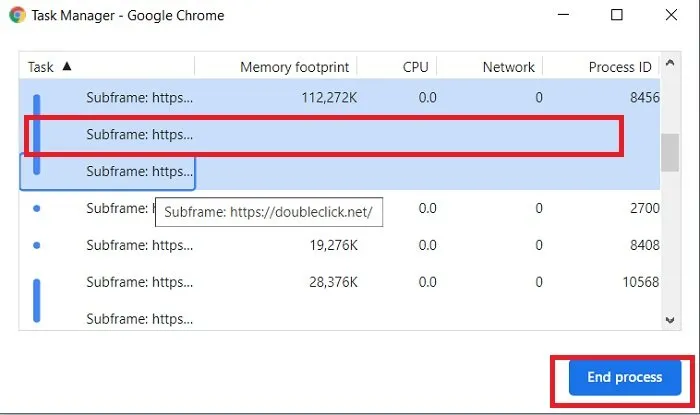

In the image, multiple tabs of the Chrome browser are opened, and you can see in Chrome’s task manager that there are multiple processes (each tab page has an independent process, along with a main process). If you are interested, you can try for yourself: if you open an extra Tab, the number of processes will normally increase by at least one.

Note: Browsers should also have their own optimization mechanism. Sometimes, after opening multiple tabs, you can see in the Chrome task manager that some processes have been combined (so it’s not always the case that each Tab corresponds to one process).

What processes does a browser include?

Knowing that the browser is multi-process, let’s see what processes it actually includes: (to simplify understanding, only the main processes are listed)

- Browser process: The main process of the browser (responsible for coordination, control), there is only one. Its functions include:

Responsible for the display of the browser interface and interaction with the user. For example, forward, backward, etc.

Responsible for the management of various pages, and the creation and destruction of other processes

Draws the Bitmap of the Renderer process obtained from memory to the user interface

Manages network resources, downloads, etc.

Third-party plug-in process: Each type of plug-in corresponds to one process, only created when the plug-in is used

GPU process: At most one, used for 3D rendering, etc.

Browser rendering process (also known as the browser kernel) (Renderer process, internally multi-threaded): By default, each Tab page is a process and they do not affect each other. Its main functions include:

- Page rendering, script execution, event handling, etc.

To enhance memory: opening a webpage in the browser is equivalent to starting a new process (a process with its own multiple threads)

Of course, the browser sometimes combines multiple processes (for example, after opening multiple blank tabs, you may find that multiple blank tabs have been merged into one process), as shown in the picture.

Additionally, you can verify this by yourself through Chrome’s More Tools -> Task Manager.

Advantages of multi-process browsers

Compared to single-process browsers, multi-process has the following advantages:

Avoids a single page crash affecting the entire browser

Avoids a third-party plugin crash affecting the entire browser

Takes full advantage of multi-core

Isolates plugins and other processes using the sandbox model, enhancing browser stability

To simplify: if the browser is single-process, then a crash on a certain Tab page would affect the entire browser, the experience would be quite poor; similarly, if it’s single-process, a plugin crash would also impact the entire browser; plus, multi-process has many other advantages…

Of course, it also consumes more memory and other resources; it’s somewhat of a trade-off between space and time.

The focus is on the browser kernel (rendering process)

Let’s focus now: we can see that, although there’re many processes mentioned above, for a regular frontend operation, what’s the most important thing? The answer is the rendering process

You can think of it this way: the rendering of the page, the execution of JS, and the event loop, all occur within this process. Let’s focus on this process next

Please remember, the browser’s rendering process is multi-threaded (if you don’t understand this point, please look back at the distinction between processes and threads).

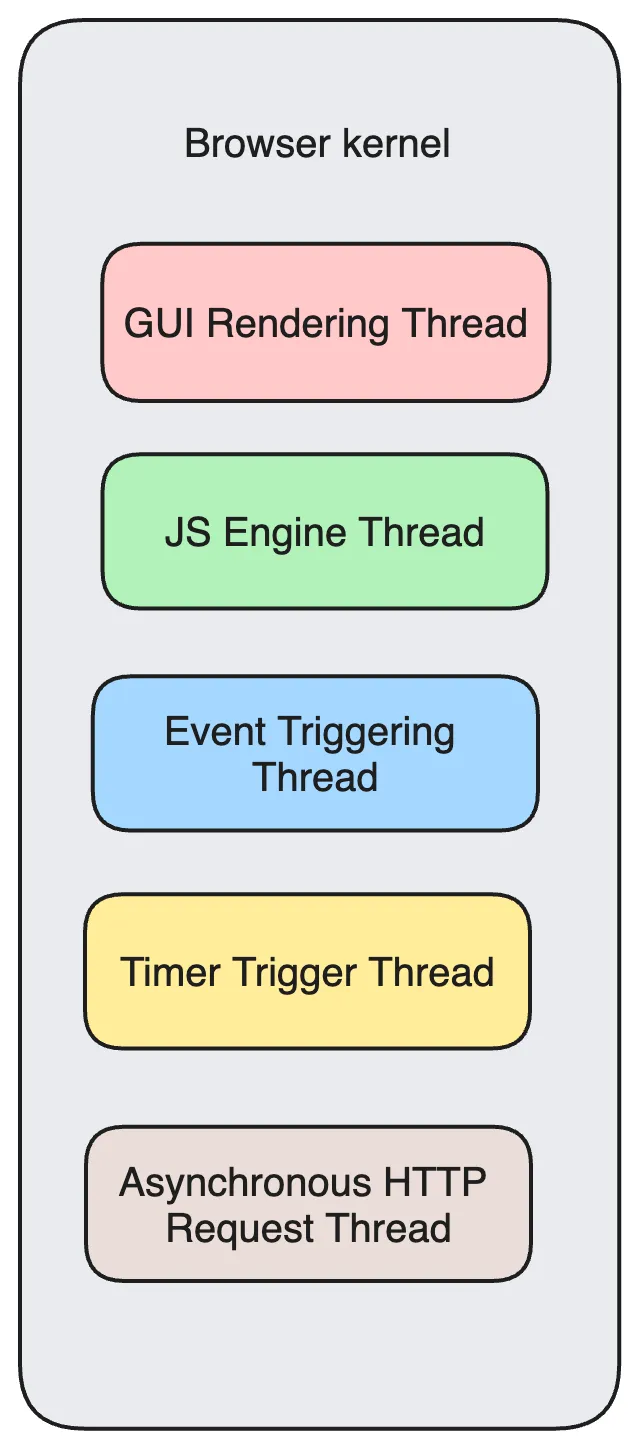

Finally, we get to the concept of threads 😭, how familiar. So, let’s see what threads it includes (listing some main resident threads):

- GUI Rendering Thread

Responsible for rendering the browser interface, parsing HTML, CSS, building DOM tree and RenderObject tree, layout, and drawing, etc.

When the interface needs to be repainted (Repaint) or a reflow is triggered due to some operation, this thread will execute

Note that the GUI rendering thread and the JS engine thread are mutually exclusive. When the JS engine is executing, the GUI thread will be suspended (as if frozen), and GUI updates will be queued to be executed immediately when the JS engine is idle.

- JS Engine Thread

Also known as JS kernel, responsible for processing Javascript scripts. (e.g., V8 Engine)

The JS engine thread is responsible for parsing Javascript scripts and running code.

The JS engine is always waiting for tasks in the task queue to arrive and then processes them. No matter when, there is only one JS thread running JS programs in a Tab page (renderer process)

Again, note that the GUI rendering thread and the JS engine thread are mutually exclusive. Therefore, if JS takes too long to execute, it will cause the page rendering to be incoherent and block the page rendering load.

- Event Triggering Thread

Belongs to the browser, not the JS engine, used to control the event loop (you can think it as the JS engine is too busy and needs the browser to help by opening another thread)

When the JS engine executes code blocks like setTimeout (or it can come from other threads of the browser kernel, such as mouse clicks, AJAX asynchronous requests, etc.), it adds the corresponding tasks to the event thread

When the corresponding event meets the trigger conditions, this thread will add the event to the end of the pending queue, waiting for the JS engine to process it

Note that due to JS’s single thread, these events in the pending queue have to line up waiting for the JS engine to process (Only when the JS engine is idle will it execute them)

- Timer Trigger Thread

The legendary thread where setInterval and setTimeout are located

The browser timer is not counted by the JavaScript engine, (since the JavaScript engine is single-threaded, if it is in a thread-blocking state, it will affect the accurate timing)

Therefore, it counts and triggers timing on a separate thread (after timing is finished, it is added to the event queue, and executed only when the JS engine is idle)

Note, W3C stipulates in the HTML standard that any time interval less than 4ms in setTimeout is considered as 4ms.

- Asynchronous HTTP Request Thread

After the connection is established in XMLHttpRequest, a new thread is opened by the browser for the request

Once a state change is detected, if a callback function is set, the asynchronous thread generates a state change event, adds this callback to the event queue again, to be executed by the JavaScript engine.

If you’re tired at this point, feel free to rest a bit, as these concepts take some time to digest. After all, the upcoming event loop mechanism is based on the event triggering thread, so if you’re just looking at a piece of information, you might have a feeling of half-understanding. It would be better to go through once to quickly settle and not forget easily. Let’s consolidate with a diagram:

Another point, why is the JS engine single-threaded? Well, this question probably doesn’t have a standard answer, such as it may simply be due to the complexity of multi-threading, like multi-thread operations generally need to be locked, so they chose single-threading in the original design…

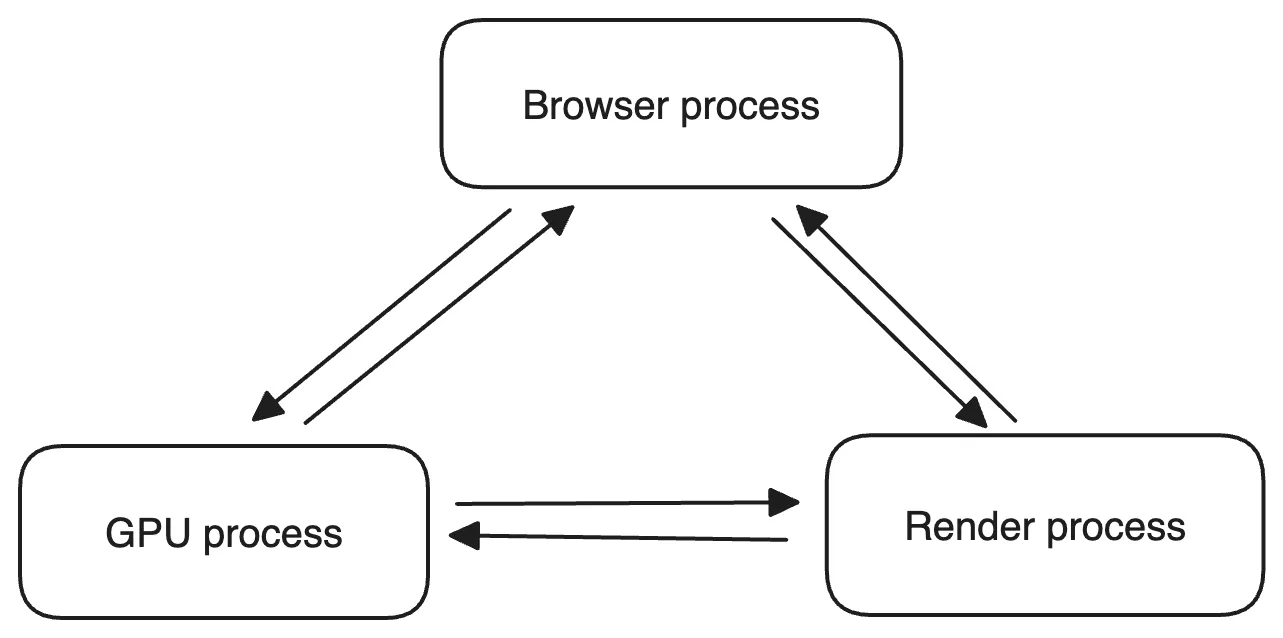

Communication process between Browser process and Browser Kernel (Renderer process)

If you’ve read this far, you should have a good understanding of the processes and threads within the browser. Next, let’s discuss how the Browser process (control process) communicates with the Kernel. After understanding this, you can connect this part of the knowledge and form a complete concept from the beginning to the end.

If you open the task manager and then open a browser, you can see: two processes appear in the task manager (one is the main control process, the other is the rendering process of the opened Tab page). On this premise, look at the whole process: (highly simplified)

The Browser process receives user requests, first needs to get page content (such as through network resource download), then passes this task to the Render process through the RendererHost interface.

The Renderer interface of the Render process receives the message, after a simple explanation, passes it to the rendering thread, and then starts to render.

The rendering thread receives the request, loads the webpage and renders it. In this process, it may require the Browser process to obtain resources and use the GPU process to assist in rendering.

Of course, there may be JS threads operating on the DOM (which could lead to reflow and repaint).

Finally, the Render process passes the result back to the Browser process.

- The Browser process receives the result and draws it.

Let’s draw a simple diagram: (very simplified)

After understanding this whole process, you should have a certain understanding of how the browser works. With this basic knowledge architecture, it will be easier to fill in the content later.

If you want to dig deep into this part, it involves the analysis of the source code of the browser kernel, which is not within the scope of this article.

If you want to dig deeper into this, it is suggested to read articles analyzing the source code of the browser kernel.

Sorting out the relationship between threads inside the browser kernel

At this point, we should have an overall concept of how the browser operates. Next, let’s simply sort out some concepts:

GUI Rendering Thread and JS Engine Thread are mutually exclusive

Since JavaScript can manipulate the DOM, if these elements are modified while rendering the interface (i.e., JS thread and UI thread running at the same time), then the element data obtained by the rendering thread before and after may be inconsistent.

Therefore, to prevent rendering from resulting in unpredicted outcomes, the browser sets the GUI rendering thread and the JS engine as mutually exclusive. When the JS engine is executing, the GUI thread will be suspended and GUI updates will be saved in a queue and executed immediately when the JS engine thread is free.

JS blocks page loading

From the above-mentioned mutual exclusion, it can be deduced that if JS takes a long time to execute, it will block the page.

For example, suppose the JS engine is performing a massive calculation, even when the GUI has updates, they are saved in the queue and will be executed only when the JS engine is free. As a result of the massive calculation, the JS engine is likely to remain busy for a long time, naturally causing a feeling of a very laggy experience.

Therefore, it’s advisable to avoid excessive JS execution times as much as possible, as this will cause the page rendering to be discontinuous, leading to a feeling of page rendering loading being blocked.

WebWorker, JS’s multithreading?

We mentioned earlier that the JS engine is single-threaded, and that if JS executes for too long it can block a page. So, is JS really powerless when it comes to CPU-intensive calculations?

Therefore, Web Worker was supported later in HTML5.

The official MDN explanation is:

Web Workers provide a simple means for web content to run scripts in background threads. The thread can carry out tasks without interfering with the user interface

A worker is an object created using a constructor (e.g., Worker()) that runs a named JavaScript file

This file contains the code that will run in the worker thread; workers run in another global context that is different from the current ‘window’

Therefore, using the window shortcut to get to the current global scope (rather than self) within a Worker will return an error

Understanding it in this way:

When creating a Worker, the JS engine requests the browser to open a sub-thread (the sub-thread is opened by the browser, completely controlled by the main thread, and can’t operate on the DOM)

The JS engine thread and the worker thread communicate through a specific way (postMessage API, it needs to serialize objects to interact with specific data)

So, if there is a very time-consuming job, start a Worker thread separately, no matter what happens in it, it will not affect the main thread of the JS engine, only need to communicate the result to the main thread after the calculation is done, perfect!

And note that the JS engine is still single-threaded, this fact has not changed, Worker can be considered as an “outside help” provided by the browser for the JS engine, specifically used to solve those heavy computing problems.

Further explanation about Worker is not the scope of this article, so we won’t elaborate further.

WebWorker and SharedWorker

Since we’re here, let’s also mention SharedWorker (to avoid confusion with WebWorker in the future)

WebWorker belongs only to some page, it won’t be shared with other pages’ Render process (browser kernel process)

So Chrome creates a new thread in the Render process (each Tab page is a render process) to run the JavaScript program in the Worker. SharedWorker is shared by all pages in the browser and can’t be implemented in the same way as Worker, because it doesn’t belong to some Render process, it can be shared by multiple Render processes

So Chrome browser creates a separate process for SharedWorker to run the JavaScript program, in the browser each same JavaScript only has one SharedWorker process, no matter how many times it is created. At this point, it should be easy to understand, essentially it’s the difference between processes and threads. SharedWorker is managed by a separate process, WebWorker is just a thread under the render process.

Briefly outline the browser rendering process

Originally, the plan was to start discussing the JS operation mechanism directly, but after some consideration, since we’ve been talking about browsers above, jumping directly to JS might seem abrupt. Therefore, I’ll supplement the rendering process of the browser (simple version) in between.

To simplify understanding, the early work is directly omitted: (If you want to elaborate or need more details, they could make up another lengthy article)

Enter the URL in the browser, the browser’s main process takes over, opens a download thread, then makes an HTTP request (omitting operations like DNS query, IP addressing, etc.), waits for the response, gets the content, then passes the content to the Renderer process through the RendererHost interface.

Browser rendering process begins

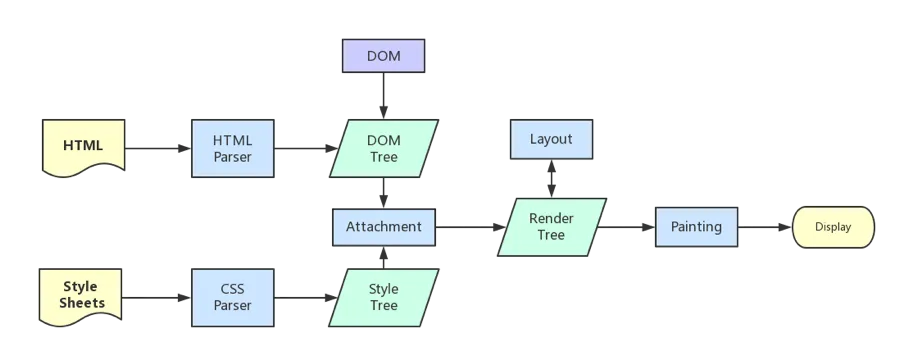

After the browser’s core gets the content, the rendering can be divided into the following steps:

Parsing HTML to build the DOM tree

Parsing CSS to build the render tree (Parse the CSS code into a tree-like data structure, then merge it with DOM to form a render tree)

Layout/render tree (Layout/reflow), responsible for the calculation of element size and position

Draw/render tree (paint), draw the pixel information of the page

The browser will send the information of each layer to the GPU, and the GPU will composite the layers and display them on the screen.

All detailed steps have been omitted. After the rendering is completed, it’s the load event, and then to your own JS logic processing.

Since we’ve omitted some detailed steps, we might as well point out some details that might need to be paid attention to.

Here’s a reference to a diagram of repainting:

The sequence of load event and DOMContentLoaded event

As mentioned above, the load event will be triggered after the rendering is complete. So, can you distinguish the sequence of the load event and the DOMContentLoaded event?

It’s easy, know their definitions:

When the DOMContentLoaded event is triggered, only when the DOM is loaded, it does not include stylesheets, images. (For example, if scripts are loaded asynchronously, they might not necessarily be completed)

When the onload event is triggered, all DOMs, stylesheets, scripts, and images have been loaded on the page. (Rendering is complete)

So, the order is: DOMContentLoaded -> load

Does loading CSS block the rendering of the DOM tree?

We’re talking about the situation of importing CSS in the header.

First of all, we all know that CSS is downloaded asynchronously by a separate download thread.

Then, let’s talk about a few phenomena:

CSS loading does not block DOM tree parsing (DOM continues to be built while loading asynchronously)

But it does block render tree rendering (Rendering needs to wait until CSS is loaded, because render tree needs CSS information)

This may also be a kind of optimization mechanism of the browser.

Because you might modify the style of the following DOM nodes while loading CSS, if CSS loading does not block render tree rendering, then when CSS is loaded, the render tree may need to be redrawn or reflowed again, which causes some unnecessary waste. So just first parse the structure of the DOM tree, finish the work that can be done, and then wait until your CSS is loaded, then render the render tree according to the final style. This approach could indeed be better performing.

Ordinary layer and composite layer

The concept of composite was mentioned in the rendering steps.

This can be simply understood as such: the layers rendered by the browser generally include two major types: ordinary layers and composite layers.

Firstly, the normal document flow can be understood as one composite layer (here called the default composite layer, regardless of how many elements are added, they are actually in the same composite layer)

Second, for absolute layout (same for fixed), although it can escape the normal document flow, it still belongs to the default composite layer.

Then, a new composite layer can be declared through hardware acceleration, which will independently allocate resources (of course, it will also get out of the normal document flow. Hence, no matter how the composite layer changes, it will not affect the reflow and repaint in the default composite layer)

This can be simply understood as such: in the GPU, each composite layer is drawn independently, so they do not affect each other. That’s also why hardware acceleration is so effective in certain scenarios.

This can be seen in Chrome source code debug -> More Tools -> Rendering -> Layer borders, where the yellow ones represent composite layer information.

How to become a composite layer (hardware acceleration)

To turn an element into a composite layer is the so-called hardware acceleration technique.

The most common way is: translate3d, translateZ

opacity attribute/transition animation (a composite layer will be created only in the process of animation execution; before the animation starts or after it ends, the element will return to its previous state)

will-change attribute (this one is quite rare), usually used with opacity and translate (and, after testing, except for the properties that can trigger hardware acceleration as mentioned above, other properties will not become composite layers), its function is to tell the browser in advance that changes will be made, so the browser will start to do some optimization work (be sure to release this once you finish using it)

Elements such as

<video> <iframe> <canvas> <webgl>Others, like the flash plugin in the past.

Difference between absolute and hardware acceleration

As can be seen, although absolute can escape the normal document flow, it cannot escape the default composite layer. So, even if the information in absolute changes and does not change the render tree in the normal document flow, during the final rendering by the browser, the entire composite layer is rendered. So, any changes in the information in absolute will still affect the rendering of the entire composite layer. (The browser will repaint it, large changes in rendering information brought by absolute with a lot of content in the composite layer can cause serious resource consumption)

And hardware acceleration just directly refers to another composite layer (“start from scratch”), so its information changes will not affect the default composite layer (of course, it will definitely affect the composite layer it belongs to internally), it only triggers the final composition (outputting the view)

What’s the role of a composite layer?

Generally, an element will become a composite layer after hardware acceleration is enabled, which can be independent of the normal document flow, and changes can avoid repainting the entire page, thereby improving performance.

But try not to use a large number of composite layers, otherwise, due to excessive resource consumption, the page may become even more laggy.

When using hardware acceleration, please use an index

When using hardware acceleration, try to use an index as much as possible to prevent the browser from defaulting to create composite layers for subsequent elements.

The specific principle is this: in webkit CSS3, if this element has added hardware acceleration and has a relatively low index level, then other elements after this element (those with a higher or same level, and with the same relative or absolute properties), will default to composite layer rendering. If not handled properly, this can greatly impact performance.

To put it simply, it’s actually an implicit composite concept: if a is a composite layer and b is on top of a, then b will also be implicitly transformed into a composite layer, which needs to be especially noted.

Discussing JS’s operation mechanism from the Event Loop

By now, it’s about things happening after the initial rendering of the browser page, and some analysis of the JS engine’s operation mechanism.

Keep in mind, I won’t be discussing execution contexts, VoiceOver (VO), scope chains, etc., (those could totally make up another article), here I’m mainly talking about how JS code is executed in conjunction with the Event Loop.

A prerequisite for understanding this part is knowing that the JS engine is single-threaded, and here I’ll use a few concepts from the text above: (If you don’t understand them quite well, you can review them)

JS engine thread

Event trigger thread

Timer trigger thread

And then understand another concept:

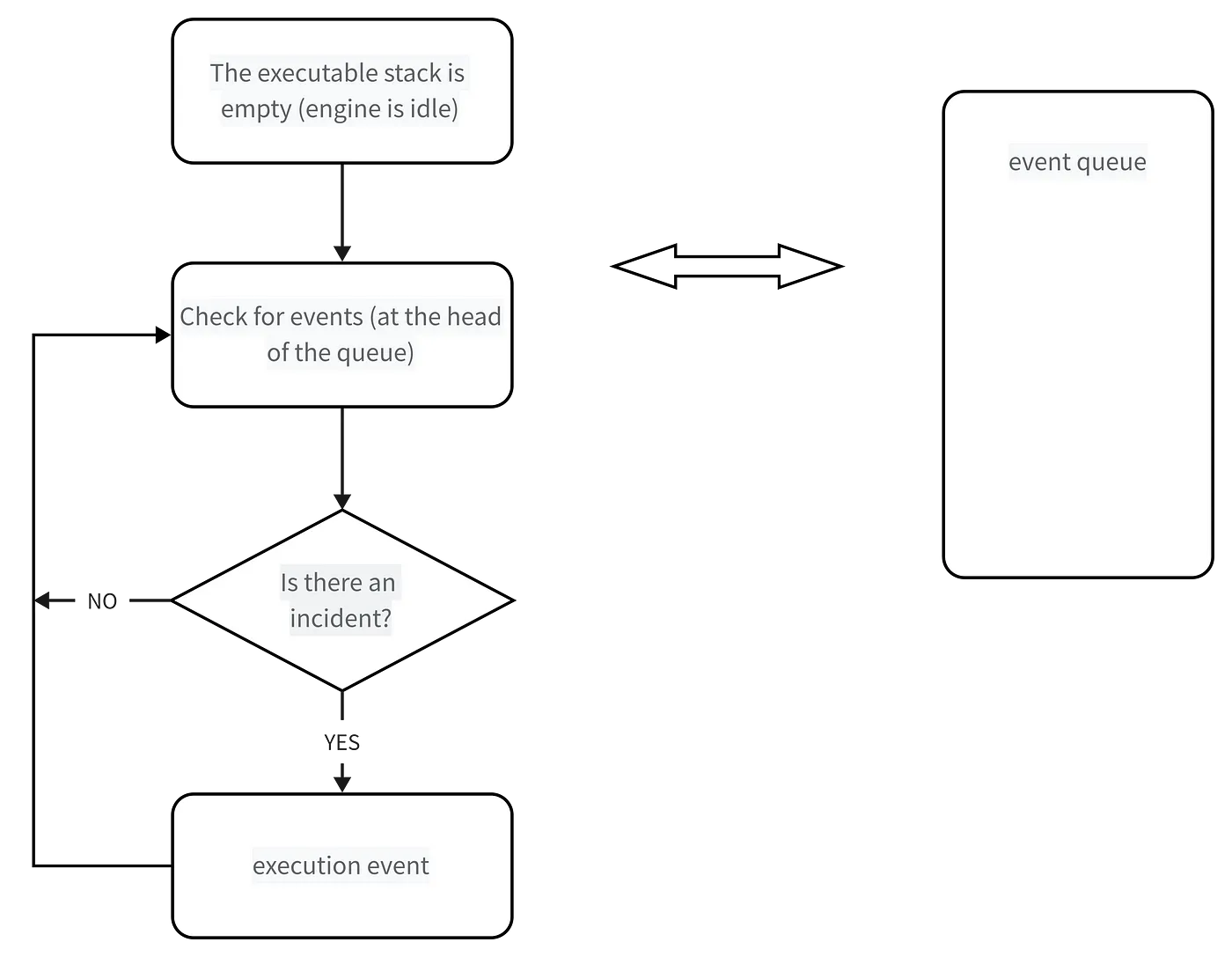

JS is divided into synchronous tasks and asynchronous tasks

Synchronous tasks are executed on the main thread and form an execution stack

Outside the main thread, an event trigger thread manages a task queue, and as long as the asynchronous task has a running result, an event will be placed in the task queue.

Once all synchronous tasks in the execution stack are completed (the JS engine is idle at this time), the system will read the task queue and add any runnable asynchronous tasks to the execution stack and start executing them.

Refer to the following diagram:

By this point, you should understand: Why can’t the events pushed by setTimeout always execute on time? Because maybe when it pushed into the event list, the main thread wasn’t idle, and it was executing other code, so naturally there could be discrepancies.

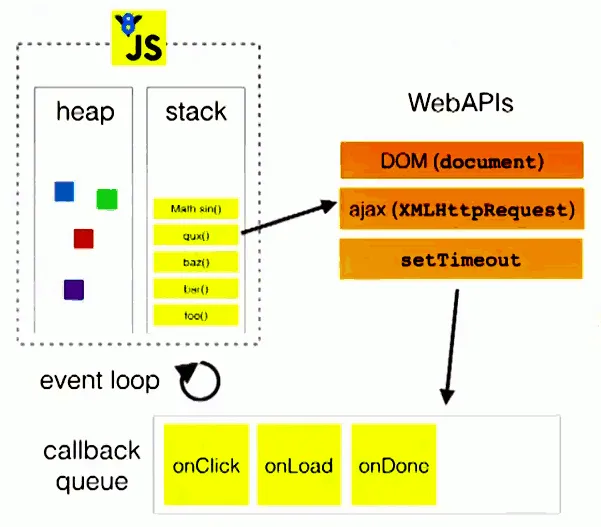

Further supplement to the event loop mechanism

Here, I’m directly referencing a diagram to assist your understanding:

The diagram roughly describes:

When the main thread runs, it generates an execution stack. When the code in the stack calls certain APIs, they add various events to the event queue (triggered when conditions are met, such as when an AJAX request is completed)

Once the code in the stack finish executing, it will read the events in the event queue and execute those callbacks

This is a loop process.

Note, you always have to wait for the code in the stack to finish executing before you read the events in the event queue.

Specifically on the timer.

The core of the aforementioned event loop mechanism is: JS engine thread and event trigger thread

But in regards to the event, there are some hidden details, for instance, after calling setTimeout, how does it wait for a specific time before adding it to the event queue?

Is it detected by the JS engine? Of course not. It is controlled by the timer thread (because the JS engine itself is too busy to multitask).

Why do we need a separate timer thread? Because the JavaScript engine is single-threaded, if it’s in a blocked thread state, it will affect the accuracy of the timing, so it’s necessary to start a separate thread for timing.

When do we use the timer thread? When using setTimeout or setInterval, it relies on the timer thread for timing. Once the timing is completed, it will push a specific event into the event queue.

For example:

| |

The function of this code is to start the timing for 1000 milliseconds (timed by the timer thread), then pushes the callback function into the event queue, waiting for the main thread to execute.

| |

The function of this code is to push the callback function into the event queue at the earliest possible time, waiting for the main thread to execute.

Note:

The execution result is: ‘begin’ first, and then ‘hello’!

Although the original intention of the code is to push it into the event queue after 0 milliseconds, the W3C stipulates in the HTML standard that a time interval less than 4ms in setTimeout should be counted as 4ms. (However, there are different opinions, stating that different browsers have different minimum time settings)

Even if it doesn’t wait for 4ms, even if it’s assumed to push into the event queue after 0 milliseconds, it will execute ‘begin’ first (because only when the executable stack is empty, it will actively read the event queue)

setTimeout instead of setInterval

Simulating regular timing with setTimeout and using setInterval directly are different.

This is because each time setTimeout times out, it will be executed, and then it will be executed for a while before continuing setTimeout, causing an error in the middle (the amount of error is related to the execution time of the code).

While setInterval is to push an event at precise intervals each time (However, the actual execution time of the event may not be accurate, and it may even happen that the next event comes before the current event finishes execution)

Moreover, setInterval has some quite fatal issues:

Cumulative effect (as mentioned above), if the setInterval code is not finished executing before it is added to the queue by setInterval again, it will cause the timer code to run continuously several times, without intervals. Even if it is executed normally at intervals, the execution time of multiple setInterval codes may be less than expected (because code execution needs some time)

Moreover, when the browser is minimized, etc., setInterval does not stop the execution of the program, it will put the callback function of setInterval in the queue, and when the browser window is opened again, it executes all at once.

So, considering so many problems, the currently generally accepted best solution is: use setTimeout to simulate setInterval, or directly use requestAnimationFrame for special occasions.

Supplement: It’s mentioned in ‘Professional JavaScript for Web Developers’ that the JS engine will optimize setInterval, if there is a callback from setInterval in the current event queue, it won’t be added again. However, there are still a lot of issues.

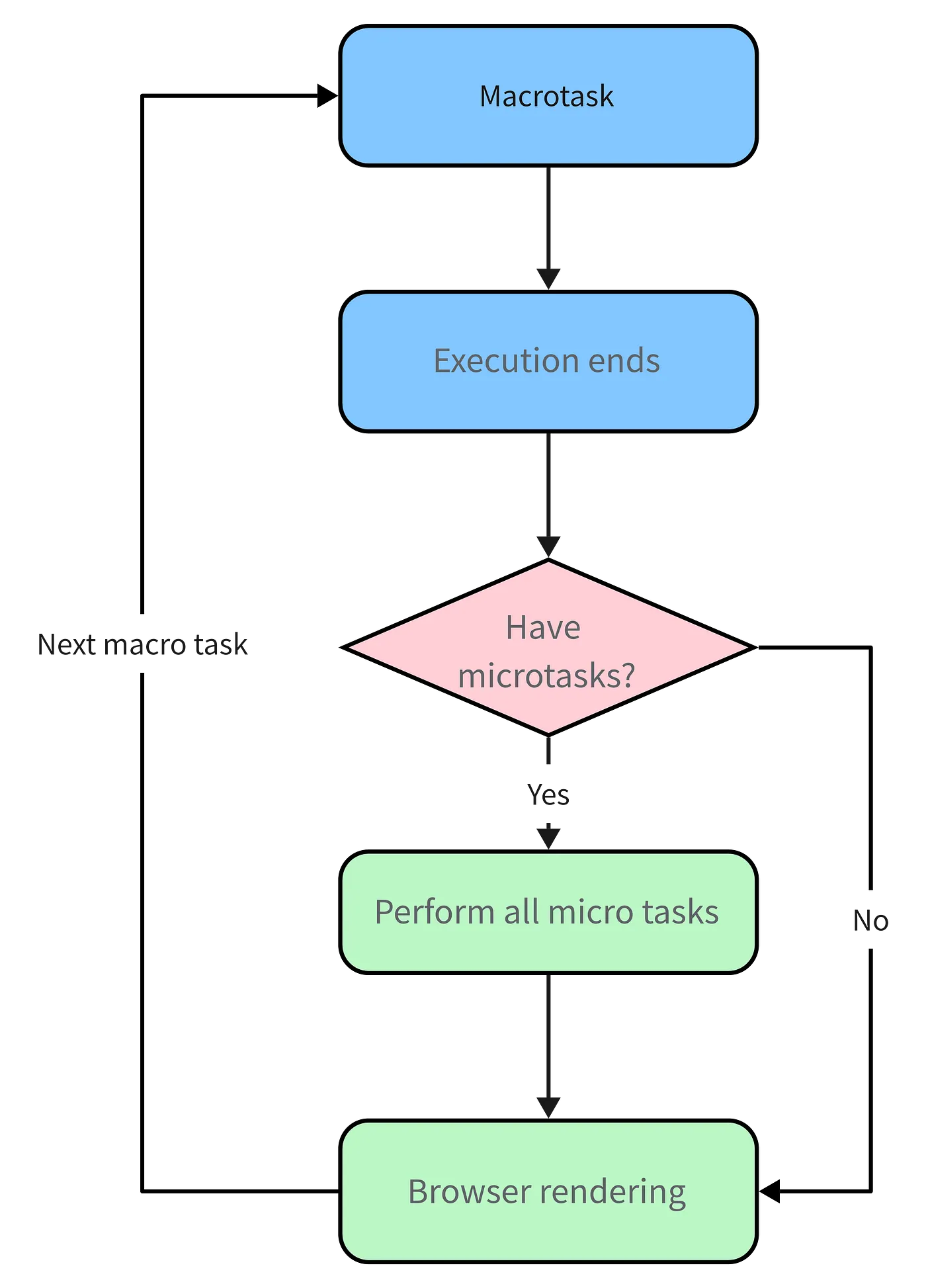

Advanced Event Loop: macrotask vs. microtask

First, let’s look at this code snippet:

| |

The correct execution order is as follows:

| |

Why? Because a new concept is introduced within Promise: microtask

Or further, JS divides into two types of tasks: macrotask and microtask, in ECMAScript, microtask is called jobs, and a macrotask can be called task

Their definition? Difference? Simply understand as follows:

- macrotask (also known as macro-task), each code block executed in the execution stack can be seen as a macrotask (including each event callback retrieved from the event queue and placed into the execution stack for execution)

Each task will execute the current task from start to finish without executing others

In order for the JS internal task and DOM task to execute sequentially, the browser will re-render the page after one task has finished and before the next task begins (task->rendering->task->…)

- microtask (also known as micro-task), tasks that are executed immediately after the current task finishes

That is to say, after the current task, before the next task, and before rendering

So its response speed is faster than setTimeout (setTimeout is a task) as it does not need to wait for rendering

That is, after a macrotask is executed, it will complete all the microtasks that were generated during its execution (before rendering)

What scenarios will form a macrotask and a microtask?

macrotask: main code block, setTimeout, setInterval, etc. (you can see, each event in the event queue is a macrotask)

microtask: Promise, process.nextTick, etc.

Supplement: In the node environment, process.nextTick has higher priority than Promise, which can be simply understood as: after the macro task ends, it first executes the nextTickQueue part in the microtask queue, then it executes the Promise part in the microtask

Let’s understand this from the perspective of threads:

Events within macrotask are all placed in one event queue, maintained by the event trigger thread

All microtasks in microtask are added to the microtask queue (Job Queues), waiting for the current macrotask to finish, this queue is maintained by the JS engine thread (it’s concluded from self-understanding and speculation, as its executed seamlessly under the main thread)

So, here’s the summary of the running mechanism:

xecute a macrotask (get from the event queue if there is none in the stack)

If a microtask is encountered during the execution, add it to the microtask queue

After the macro-task finishes, immediately execute all microtasks in the current microtask queue (one by one)

After the current macrotask finishes, start checking for rendering, then the GUI thread takes over rendering

After rendering, the JS thread takes over again, starting the next macrotask (getting from the event queue)

As illustrated:

Also, please note the difference between Promise’s polyfill and the official version:

In the official version, it is a standard microtask form

polyfill, usually simulated by setTimeout, so it is macrotask form

Please particularly note these two differences

Note, some browsers have different results (because they may treat microtask as macrotask), but for simplicity, some non-standard browser scenarios are not described here (but remember, some browsers may not be standard)

Implementing microtask with MutationObserver

MutationObserver can be used to implement microtasks (it’s considered a microtask with lower priority than Promise, it’s generally used when Promise is not supported)

It’s a new feature in HTML5, its function is: to monitor a DOM change. When any change occurs in the DOM object tree, Mutation Observer will be notified.

For instance, in the previous Vue source code, it was used to simulate nextTick. The specific principle is to create a TextNode and monitor its changes. Then, when nextTick is performed, change the text content of this node. As shown:

| |

However, later versions of Vue (2.5+) removed the MutationObserver way from nextTick’s implementation (presumably due to compatibility reasons), and instead used MessageChannel (of course, the default is still Promise, with compatibility as backup).

MessageChannel is a macrotask, and its priority is: MessageChannel -> setTimeout, so the internal nextTick of Vue (2.5+) is different from the implementation of 2.4 and before. That’s something you should be aware of.

Conclusion

Having read this far, I’m not sure if you have a better understanding of JS’s operating mechanism, but going through it all from start to finish, rather than just a fragmentary piece of knowledge, should definitely clear things up?

At the same time, it’s also worth noting that JS is not as simple as you might think it is, front-end knowledge is infinite, with endless concepts, a ton of easily forgotten knowledge points, all kinds of frameworks, and the underlying principles that can be endlessly delved into. Then, you’ll find out that what you know is too little…